Views on Error Handling

In this post, I summarize some accomplished engineer’s views on error handling. There is a distinction between errors that are caused by programmer neglecting bugs and those that represent true error conditions. The granularity of error checking is also up for debate: Per function? Per module? Jump to dialog handler in the main message loop? Kill the process and restart?

The Midori Error Model

Joe Duffy describes in The Error Model the considerations that went into designing error handling in Midori. He said that they were guided by these principles:

- Usable. It must be easy for developers to do the “right” thing in the face of error, almost as if by accident. A friend and colleague famously called this falling into The Pit of Success. The model should not impose excessive ceremony to write idiomatic code. Ideally, it is cognitively familiar to our target audience.

- Reliable. The Error Model is the foundation of the entire system’s reliability. We were building an operating system, after all, so reliability was paramount. You might even have accused us as obsessively pursuing extreme levels of it. Our mantra guiding much of the programming model development was “correct by construction.”

- Performant. The common case needs to be extremely fast. That means as close to zero overhead as possible for success paths. Any added costs for failure paths must be entirely “pay-for-play.” And unlike many modern systems that are willing to overly penalize error paths, we had several performance-critical components for which this wasn’t acceptable, so errors had to be reasonably fast too.

- Concurrent. Our entire system was distributed and highly concurrent. This raises concerns that are usually afterthoughts in other Error Models. They needed to be front-and-center in ours.

- Diagnosable. Debugging failures, either interactively or after-the-fact, needs to be productive and easy.

- Composable. At the core, the Error Model is a programming language feature, sitting at the center of a developer’s expression of code. As such, it had to provide familiar orthogonality and composability with other features of the system. Integrating separately authored components had to be natural, reliable, and predictable.

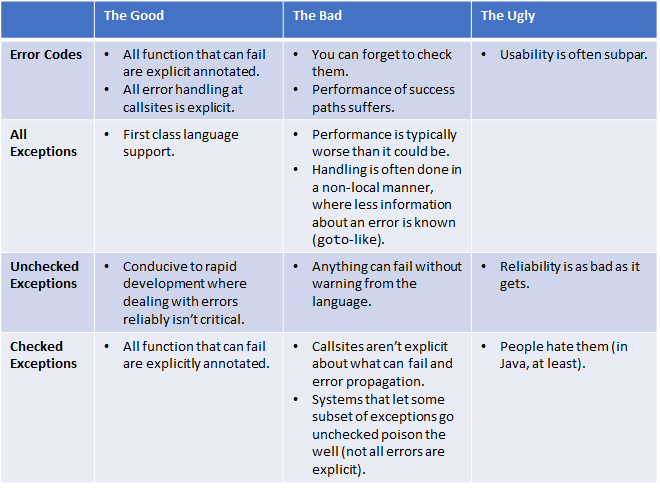

Joe compared different error models against these criteria and came up with the table below:

In the end, he chose checked exception but separated all programmer-error cases. Those were handled by abandonment - deadly asserts. The compiler could optimize the code better since it knew exactly which paths could throw (in contrast to C++ where you have to annotate each function that can not throw). The syntax is similar to what is now found in Swift and Rust.

The Erlang Approach - Let it Crash

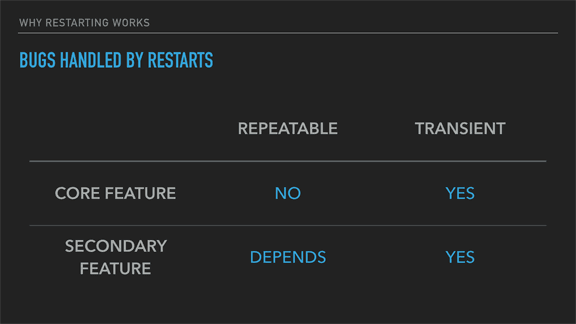

The Erlang folks are a bit more hardcore. They don’t get bogged down in discussions about syntactic structures. Joe Armstrong says in Dos and Don’ts of error handling: “You’re correctness theorems aren’t gonna help you if your computer is hit by lightning. What he meant is that no system runs in isolation and there’s always the chance of failure. So when errors do happen, they restart the affected process to a known state and try again.

Fred Hebert describes in The Zen of Erlang the Let it Crash motto. Erlang processes are fully isolated and share nothing. So if an error is detected, the system just kills the process and restarts. But how can that solve anything? Won’t the same bug just happen over and over again? How to deal with a configuration file that has the wrong content?

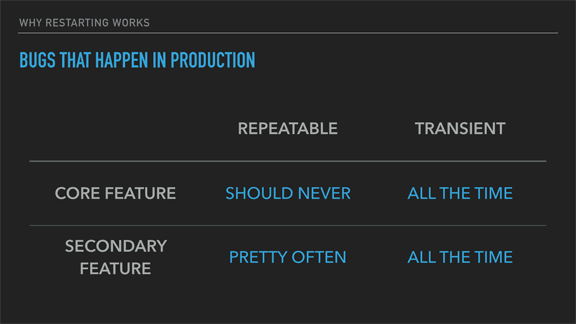

Fred refers to Jim Grays 1985 paper Why Do Computers Stop and What Can Be Done About It?. There Gray introduces the notion of Heisenbugs and Bohrbugs. In Fred Hebert’s words:

Basically, a bohrbug is a bug that is solid, observable, and easily repeatable. They tend to be fairly simple to reason about. Heisenbugs by contrast, have unreliable behaviour that manifests itself under certain conditions, and which may be hidden by the simple act of trying to observe them. For example, concurrency bugs are notorious for disappearing when using a debugger that may force every operation in the system to be serialized.

Heisenbugs are these nasty bugs that happen once in a thousand, million, billion, or trillion times. You know someone’s been working on figuring one out for a while once you see them print out pages of code and go to town on them with a bunch of markers.

So a repeatable (Bohr) bug will be easy to reproduce while a transient (Heisenbug) will be hard. Now, Hebert argues that if you have a bohrbug in your system’s core features it should be very easy to find before reaching production. By being repeatable and often on a critical path, you should encounter them sooner or later, and fix them before shipping.

Now, Jim Gray’s paper reports that transient errors (heisenbugs) happen all the time. They are often fixed by restarting. As long as you weed out the bohrbugs by having proper testing of your releases, the remaining bugs are often solved by restarting and rolling back to a known state.

Classification of Exceptions

Eric Lippert gives this taxonomy in Vexing Exceptions

- Fatal exceptions are not your fault, you cannot prevent them, and you cannot sensibly clean up from them. They almost always happen because the process is deeply diseased and is about to be put out of its misery. Out of memory, thread aborted, and so on.

- Boneheaded exceptions are your own darn fault, you could have prevented them and therefore they are bugs in your code. You should not catch them; doing so is hiding a bug in your code. Rather, you should write your code so that the exception cannot possibly happen in the first place, and therefore does not need to be caught. That argument is null, that typecast is bad, that index is out of range, you’re trying to divide by zero

- Vexing exceptions are the result of unfortunate design decisions. Vexing exceptions are thrown in a completely non-exceptional circumstance, and therefore must be caught and handled all the time. The classic example of a vexing exception is Int32.Parse, which throws if you give it a string that cannot be parsed as an integer. Eric recommends calling the Try versions of these functions instead.

- Exogenous exceptions appear to be somewhat like vexing exceptions except that they are not the result of unfortunate design choices. Rather, they are the result of untidy external realities impinging upon your beautiful, crisp program logic.

Eric gives this pseduo-C# example:

try {

using ( File f = OpenFile(filename, ForReading) ) {

use(f);

}

} catch (FileNotFoundException) {

// Handle filename not found

}

Can you eliminate the try-catch with this code?

if (!FileExists(filaname))

// Handle filename not found

else

using (File f = ...

No, you can’t! The new code has a race condition. Eric suggests that you just bite the bullet and always handle exceptions that indicate unexpected exogenous conditions.

Composing Errors Codes

Rob Pike writes in Errors are

Values about how to avoid writing

if err != nil {...} all the time in Go code. Instead of sprinkling if

statements, the error handling can be integrated into the type. He gives the

bufio packages’s Scanner as an example:

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(input)

for scanner.Scan() {

token := scanner.Text()

// process token

}

if err := scanner.Err(); err != nil {

// process the error

}

The check for errors is only done once. Rob also mentions that the

archive/zip and net/http packages use the same pattern. The bufio

package’s Writer does as well.

b := bufio.NewWriter(fd)

b.Write(x)

b.Write(y)

b.Write(z)

// and so on

if b.Flush() != nil {

return b.Flush()

}

Fabien Giesen describes a similar pattern for error handling in Buffer Centric I/O. And the pattern is used extensively throughout the Qt framework’s core classes. Another name for it is sticky errors or error accumulator.

Error Handling Granularity

Per Vognsen discusses how to do course-grained error handling in C using setjmp/longjmp. The use case there were for arena allocations and deeply nested recursive parsers. It’s very similar to how C++ does exception handling, but without the downsides of the costly C++ memory deallocation on stack unwinding. He goes on to say that certain classes of push-oriented API’s, that has clear command-query separation, don’t need to do fine-grained error handling. It’s the same idea as in the previous section.

Fabien Giesen describes in an aside for a gist note how he views error handling. He points out that it may be beneficial to only provide a small set of error codes and that the selection of those should be dictated by the question “what should I do next?”. E.g. there are many ways a network connection can fail but providing a giant taxonomy of error codes won’t help the calling code to decide what to do. Logging should be as specific as possible but the users of an API just need to decide what to do next.

Fabien wrote in a blog comment that having stack unwinding do the cleanup on errors is a bad design that costs lots of resources and is hard to control.

“Cleanup stack”-based unwinding incurs a cost on every single function, which means it’s equivalent to checking for error conditions in every single function. That is a very bad way of implementing error handling; a method that works much better is to just remember that an error occurred, but substitute valid data as soon as possible.

That is, separate “tactical” error handling (which just needs to make sure your program ends up in a safe and consistent state) from “strategical” error handling (which is usually at a pretty high level in an app and might involve user interaction), and try to keep most intermediate layers unaware of both.

I consider this good practice in general, not least because immediately escalating error conditions not only makes for hard to understand control flow, but also a bad user experience. Take broken P4 connections, copies of large directories, things like that. Asking me on every single problem is just poor design, but it reflects the underlying model of the application reacting to every error code. Unless there’s no way you can sensibly go on, just make a list of things that went wrong and show it to me at the end. That’s not just a better user experience, it also tends to be quite easy if it’s designed in from the beginning.

Summary

The first thing to ask yourself when designing error handling, is what granularity is required? If you have a 10KLOC parser and it is allowed to give up when it encounters the first error, then that is an easier problem to solve than a parser that should continue the parsing at some synchronization point. Can you just throw away the stack, or exit the process then that’s easier than trying to get the process back into a known state by unwinding the stack.

Error codes can be ignored! That’s a solved problem in Rust, but the two other recent systems programming languages Go and Swift does not AFAICT provide mechanisms for enforcing checks of return types.

The line between programmer bugs and genuine errors is hard to draw: Java has checked exceptions but introduced RuntimeException to deal with indices out of bounds, illegal arguments, and so forth. Go and Rust both have a separate panic statement for critical bugs.

The line between errors and regular, to be expected, return values has tripped up many. C# and Java used exceptions for signaling that an integer could not be parsed! Those “vexing exceptions” should never have been exceptions.

It is hard to fulfill all of Joe Duffys criteria. Erlang is usable, reliable, concurrent, diagnosable, and composable but it is slow compared to the alternatives. C and Go are reliable and concurrent but it fails on the usable criteria: it’s easy to ignore a return value. As for composability: Many languages have introduced special syntactic forms for handling errors, but with stick error patterns surprisingly much can be achieved using just return values. C++ exceptions fails the diagnosable criteria (no stacktraces) and usability (it’s easy to write code that doesn’t handle exceptions that should be handled).